In the movie Interstellar, the protagonist embarks on a space mission for the future of humanity. From a five-dimensional space, he sends a signal across time to his daughter on Earth. Even today, humanity receives time-transcending messages from the universe. The light emitted endlessly by the stars in the night sky—sent from the past and arriving in our present—is precisely that signal.

The vast universe is filled with countless stars1 and galaxies, each radiating its own light. Yet from Earth, we cannot see the universe as it exists now. We see the Sun as it was eight minutes ago, and we navigate by the North Star as it appeared 466 years ago. What messages does this starlight—having traveled across space and time—bring to us?

1. Star: In this context, “star” refers to an astronomical object, specifically a celestial body (a stellar object) that generates its own light through internal energy radiation.

The Messenger of Information From the Universe

Among all human senses, vision is dominant—and light is essential for sight because it stimulates the optic nerve.

Light spans a wide range of wavelengths, from visible light to ultraviolet, infrared, and X-rays. Visible light allows us to recognize physical features like facial shape, skin tone, and body size. Infrared light reveals heat patterns, while X-rays expose bone structure. Depending on the wavelength, light uncovers different aspects of the same object.

Without light, we are blind. In darkness, we can still grope our way forward through touch, smell, or sound. But the distant universe offers no such alternatives—we cannot touch it or hear it. That is why starlight is so extraordinary: It is our only messenger from the cosmos.

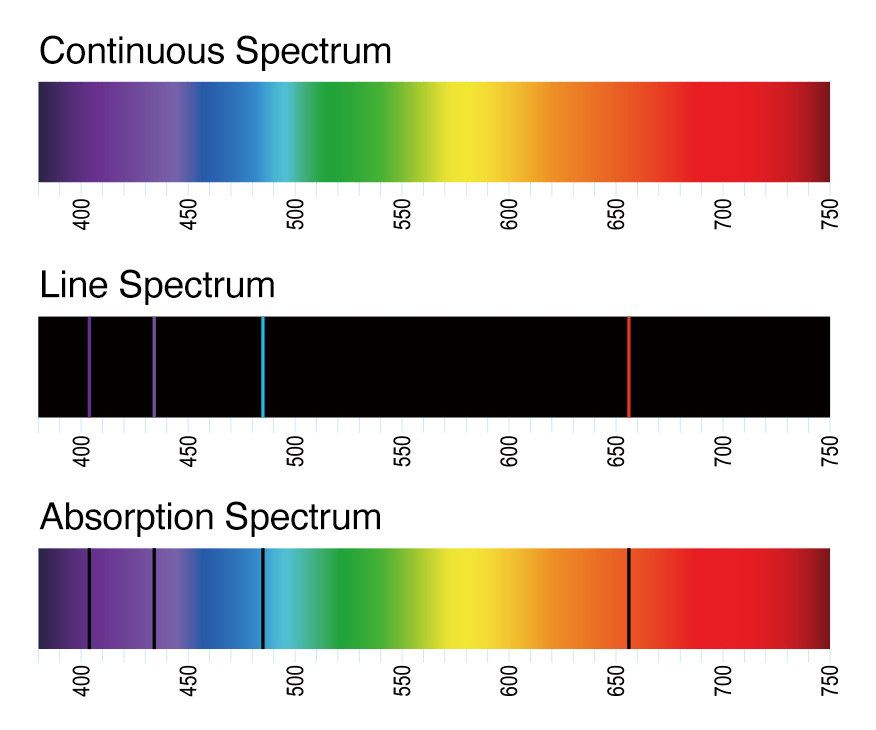

Nearly everything we know about the universe—distances to stars, their masses, brightness levels, surface temperatures, rotation speeds, chemical compositions, and even their ages—has been uncovered through the study of light. When light passes through a prism, it refracts and separates into a spectrum—a band of colors spread according to wavelength. At this time, each star displays a unique spectrum whose line positions and thicknesses vary depending on its elemental composition and surface temperature.

By analyzing a star’s spectrum, we can determine its elemental makeup and temperature without ever leaving Earth. A star’s temperature also hints at its color, mass, and internal pressure, revealing even more information. Light released when a supernova explodes can reveal the composition of the galaxy to which the star belongs. And the Doppler effect—where wavelengths shift as an object approaches or recedes—allows us to determine its orbital period and other properties. Because of this wealth of information, astronomers often call a star’s spectrum the “fingerprint of the sky.”

No Matter How Fast—Still Within the Universe

We often say something happens “in the blink of an eye” to describe how quickly it occurs. A blink lasts about 0.1 seconds. Light—the fastest known entity in the universe—travels 300 million times faster than a blink, racing through space at approximately 300,000 kilometers (186,282 miles) per second. At that speed, it could circle Earth seven and a half times in just one second. While Apollo 11 took more than four days to reach the Moon, light would arrive in a single second. Because light is so unimaginably fast by human standards, people once believed its speed was infinite.

And yet, even light has limits—especially in space. Before modern communication, people had to send messages by horseback. No matter how fast the horse ran, delivering the message still took days or weeks, depending on the distance. In a similar way, although light travels at an extraordinary speed without rest, it still needs time to cross the immense expanses of the universe. Light requires two full years just to leave our solar system. The universe is so vast that even light cannot escape the constraints of time and distance.

If you hold a coin and slowly extend your arm, the coin appears smaller. The Sun, whose surface area is more than 10,000 times that of Earth, looks no larger than a coin in the sky—simply because of its distance. Earth is about 150 million kilometers from the Sun, a distance defined as 1 Astronomical Unit (AU). Traveling at light speed, the journey takes eight minutes. A rocket would need about 155 days, and if someone could walk the distance, it would take 3,424 years. As enormous as 1 AU sounds, it is tiny in cosmic terms and mainly used for measuring distances within the solar system.

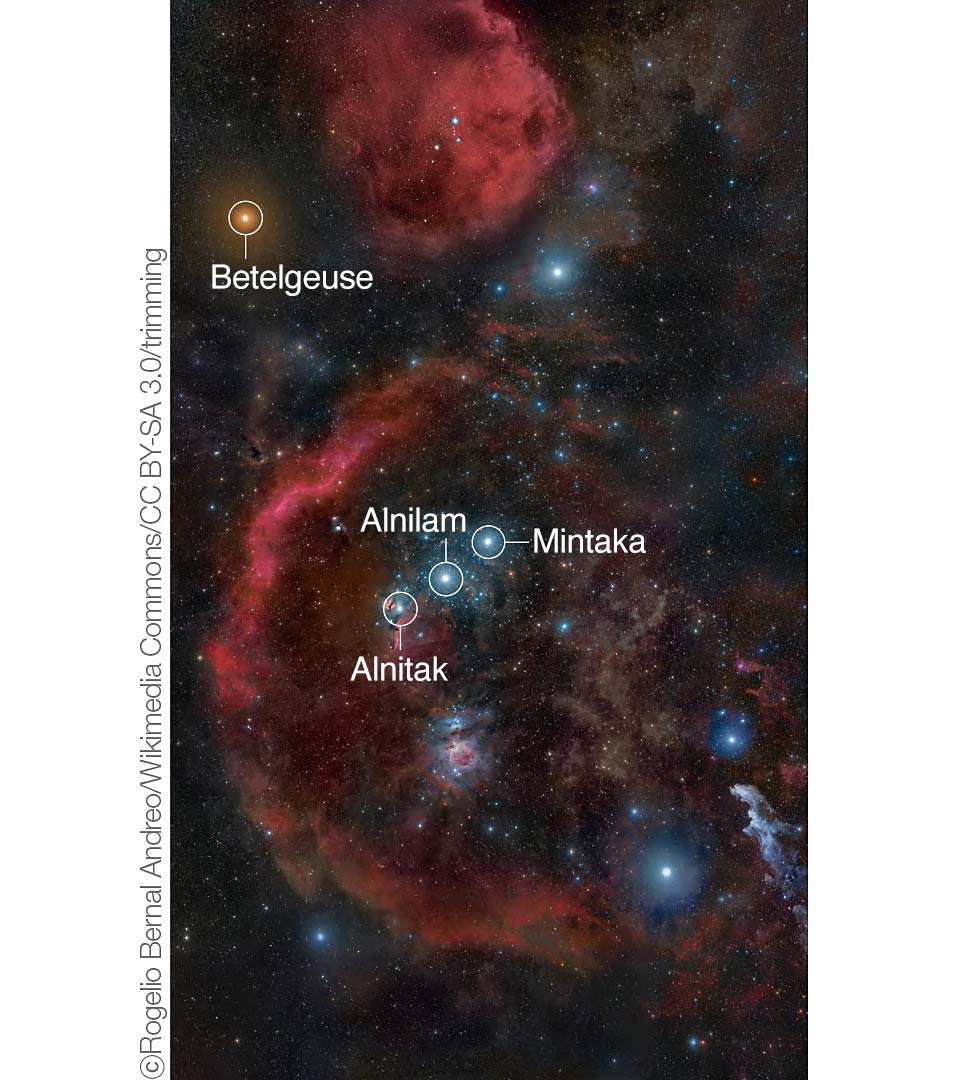

Proxima Centauri, a star in the constellation Centaurus, is the closest star to Earth after the Sun. Yet even Proxima lies around 268,400 AU away—more than four light-years2. Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, is 8.7 light-years from Earth. The three stars of Orion’s Belt—Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka—are roughly 800, 2,000, and 1,200 light-years away, respectively. And these are still considered “nearby” on a cosmic scale. The universe is filled with celestial bodies so distant that even light would require thousands or millions of years to reach them.

2. Light-year: A unit of distance used in astronomy. It represents the distance that light travels in one year. One light-year equals approximately 9.46 trillion kilometers (5.88 trillion miles). To reach this distance on foot without stopping, a person would need to walk for 225 million years.

The Universe’s Footprints Imprinted in the Sky

When you walk across a sandy beach and look back, you see the footprints you have left; the farther away they are, the longer ago they were made. Likewise, the greater the distance to a celestial object, the older the state of the universe that its light reveals to us. Starlight is, in essence, the universe’s footprints stamped across the sky. As we have seen, starlight carries a remarkable wealth of information. The deeper and farther we look into space, the further back in time we peer—tracing the universe’s story from its maturity all the way to its earliest infancy.

It takes light eight minutes to travel from the Sun to Earth, which means the sunlight we experience is already eight minutes old. The light we saw from Sirius today actually left the star 8.7 years earlier. The North Star, a steadfast guide for countless travelers and sailors, shines with light that began its journey 466 years ago. And the light from the Andromeda Galaxy—emitted 2.5 million years ago—is only now reaching us. By observing the light from other galaxies and analyzing their morphology and evolutionary stages, we can infer how our own Milky Way has developed over time. Astronomers expect that by detecting light from even earlier epochs, they may one day identify the universe’s first stars and galaxies and uncover clues about the origin of the cosmos 13.8 billion years ago.

Yet even when we observe galaxies billions of light-years away, what we see may not reflect present reality. Their light has traveled for so long that it shows them not as they are now, but as they once were. We may, in fact, be looking at the fading light of stars that no longer exist.

What You See Is Not All There Is

Across the universe, countless stars—like grains of sand along a shoreline—are shining at this very moment. If that is true, then why isn’t the night sky overflowing with light? Why do we see mostly darkness?

The answer lies in distance. The farther a star is, the fainter its light becomes.3 And because the typical distance between galaxies exceeds one to two million light-years, much of their light fades beyond visibility. To our eyes, the sky remains dark. But if we could see as deeply as a radio telescope4—capable of detecting extremely faint, distant signals—the night sky would appear crowded with stars and galaxies, filling the darkness with light we cannot normally perceive.

3. A star’s brightness is inversely proportional to the square of its distance.

4. Radio Telescope: A device used to observe radio waves emitted by celestial objects. Unlike optical telescopes, which collect visible light, radio telescopes detect radio frequency radiation from space, allowing astronomers to observe and measure celestial bodies more precisely.

We often imagine stars twinkling in the night sky, just as the nursery rhyme Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star describes. But stars do not actually twinkle. Their light only appears to shimmer because it wavers and scatters as it passes through Earth’s atmosphere. In fact, Earth’s atmosphere makes observing many celestial objects extremely difficult. It absorbs or blocks nearly all types of light except visible and radio wavelengths.

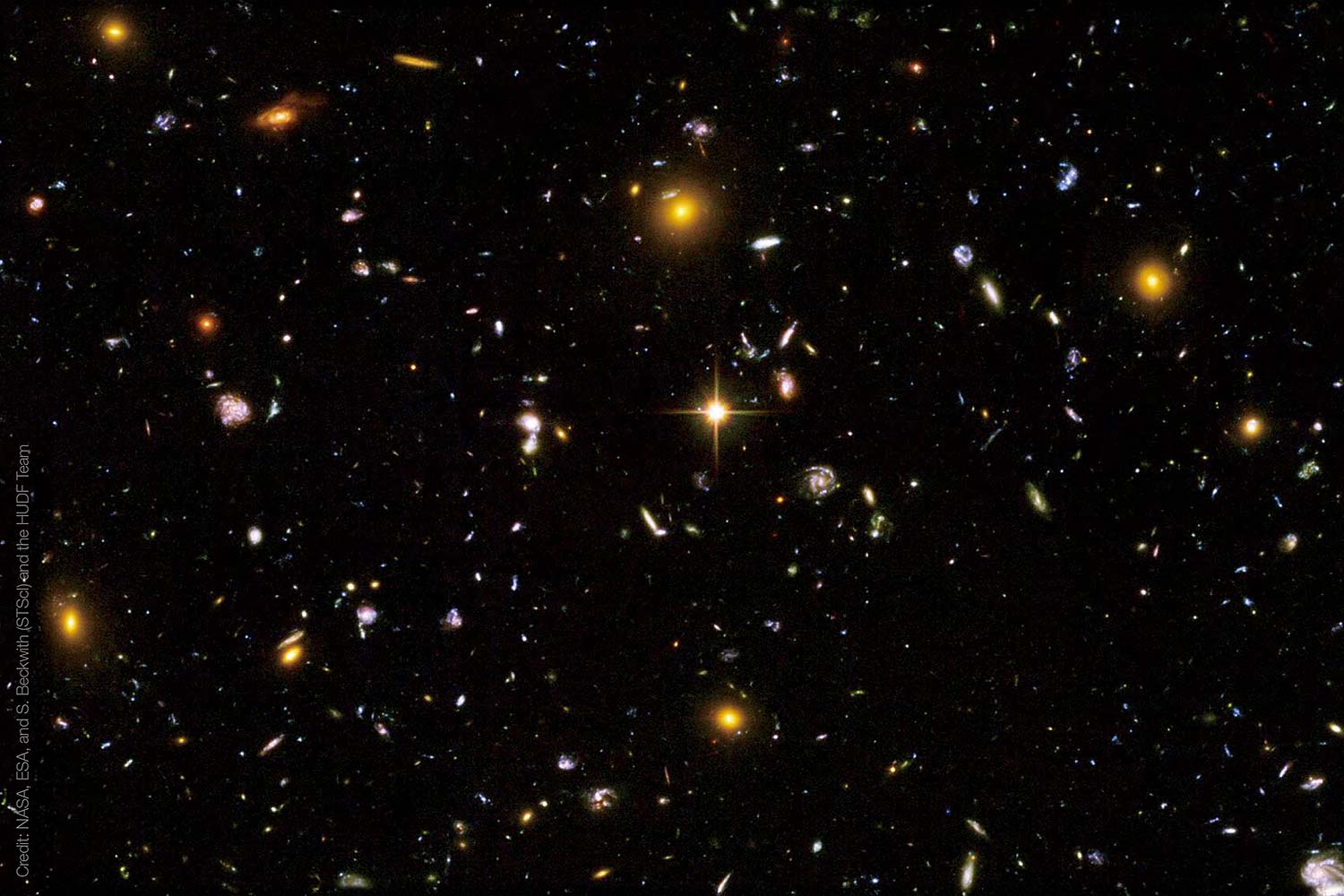

To observe the universe without the distortions caused by Earth’s atmosphere, scientists launched an “artificial eye” into space—the Hubble Space Telescope. Initially designed to study galaxies, stars, and planets, Hubble soon reshaped our understanding of the cosmos. In 1995, astronomers used it to observe a dark, seemingly empty region of the sky—an area where nothing could be detected from the ground. By collecting every faint photon from this tiny, pinhole-sized patch, Hubble revealed an astonishing result: more than 3,000 galaxies. Wherever they pointed the telescope, the same pattern emerged—dark, empty space was actually filled with galaxies. Astronomers named this region the Hubble Deep Field (HDF). Thanks to advances in space-based observational technology, our perception of the night sky—and of the universe once thought empty—was fundamentally transformed.

Hubble has since gone even deeper. In its Ultra Deep Field (HUDF) and eXtreme Deep Field (HXDF) images, it captured nearly 10,000 galaxies within a region smaller than the eye of a needle. Each galaxy contains, on average, about 200 billion stars. It is nearly impossible to imagine how many stars fill the universe when such a tiny patch of sky holds so many.

From the farthest reaches of time and space, starlight continues to send its signals to Earth. Contained within that light is a universe far more vast and mysterious than we can fully comprehend. Even now, humanity follows those faint traces of light, learning more about the cosmos without ever leaving our planet.

Meanwhile, the universe continues to expand, with more distant regions receding at increasingly faster rates. Someday, some galaxies may recede faster than the speed of light, placing them beyond the reach of even the most advanced telescopes. What remains certain is this: The scale of the universe—vast enough to render even light finite—far surpasses the limits of human senses and imagination.

“Light is sweet, and it pleases the eyes to see the sun.” Ecclesiastes 11:7

“Is not God in the heights of heaven? And see how lofty are the highest stars!” Job 22:12